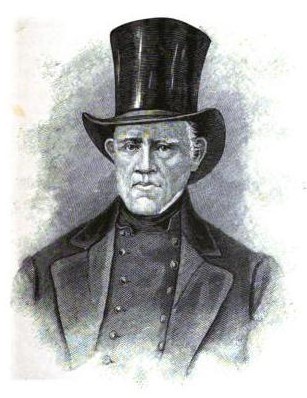

Judah Touro was born on June 16, 1775, in New Port, Rhode Island. His family moved to New York in 1780 after the British captured Newport, and then to Kingston, Jamaica in 1782. His father died a year later and his mother moved the family to Boston to live with her brother, Moses Michael Hays, a merchant and philanthropist who helped founded Boston’s first bank. When his mother died in 1787, Touro and his siblings were raised by his uncle.

In October 1801, Touro moved to New Orleans where he opened a small store selling soap, candles, codfish, and other exports from New England. He eventually became a prominent merchant and shipowner, particularly after the Louisiana Purchase in 1903 which caused a large growth of the region and its economy. Despite being unable to fight, Judah enlisted in Andrew Jackson’s army in the War of 1812, volunteering in the Battle of New Orleans to carry ammunition to the batteries when he was struck in the thigh by a twelve-pound cannonball, tearing off a large chunk of flesh. Left for dead, he was saved by fellow merchant Rezin Davis Shepherd who nursed Touro back to health and remained friends throughout their lives. After the war, Touro continued building his business interests in trade, shipping, and real estate. He remarked that his fortune came from living a simple life instead of a lavish one, as he lived in a small apartment and never mortgaged properties to acquire new ones. Touro was a philanthropist whose contributions are still remembered and honored to this day. In New Orleans, he opened an infirmary for sailors suffering from yellow fever and a synagogue, now the United States’ oldest synagogue outside of the original thirteen colonies.

After his death in 1854, his bequeathed his $1 million estate to various causes, about $27 million in today’s economy. One of his requests was the establishment of an almshouse for the elderly poor in the city.

The Touro Almshouse was incorporated in 1855 and the executors of his estate acquired land donated by Rezin Davis Shepherd, Touro’s lifelong friend. A towering Gothic structure, the building was designed by

William Alfred Freret Jr. and completed in April 1862. That same month, Union troops captured New Orleans without resistance and occupied the Touro Almshouse, filling it with gun racks, provisional beds, and a kitchen. The almshouse would become the official headquarters for the native guards which included the Union Army’s 1st Louisiana Native Guard, a fighting force of over 1,000 men composed mostly of African-American former slaves who had escaped to freedom. After the Confederate surrender in April 1865, Union officials had planned to vacate the almshouse by September 1st, 1865, as it was no longer needed. On the last day of their occupancy, troops were cooking baked beans in the kitchen when sparks ignited combustible materials in the makeshift air duct they had used for the kitchen. The fire spread quickly as the tar roof ignited, and by morning, Touro’s Gothic almshouse was in ruins.

Due to public interest in Touro’s first almshouse, a second building was constructed in 1895 in Uptown, funded through Mayor Joseph A. Shakspeare’s gambling tax. As the area became more populated, the uptown site was subdivided into residences in 1927 and the facility was relocated to Algiers. Named the Touro-Shakspeare Almshouse, the new building was built in 1933 and designed by William R. Burk, who was quoted in 1929 that his design “calls for a building that is as beautiful and dignified as a private residence, but which also bears the stamp of being a municipal building.” The building remained in operation for 72 years, serving as the city’s almshouse and then as a senior care facility managed by Touro Shakspeare Inc., but still owned by the City of New Orleans just as Touro envisioned it. Due to damages sustained during Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the Touro-Shakspeare Home was shuttered and would never

reopen.

In 2009, Jahncke & Burns Architects was contracted with designing a restoration plan for the building. The contract was extended to include supervision of the construction, but the City of New Orleans ultimately abandoned the project, leaving the building in a state of ruin. In 2016, the City successfully appealed to FEMA to draft a Section 106 Review in order to mothball the property. FEMA agreed that they would provide funding for the removal of lead paint, mold and asbestos, the removal of debris and non-historic building materials, and the installation of security measures. Despite this, the project has not begun with no future commencement date. With the amount of FEMA fraud that occurred in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina, it would be unsurprising if someone simply pocketed the money intended for the building’s restoration.