St. Elizabeths Hospital was first founded in August 1852 when the United States Congress ordered for the construction of a hospital in Washington D.C. to care for the indigent residents of the District of Columbia and members of the U.S. Army and Navy with brain illnesses. Opening in 1855 as the Government Hospital for the Insane, the name St. Elizabeth’s Hospital was used by the U.S. Army during the Civil War in order to differentiate themselves from the psychiatric hospital which occupied the building’s west wing while the Army occupied the east wing. After the war, the name continued to be unofficially used until 1916, when Congress passed legislation to change the name to St. Elizabeths. In the early 20th century, Blackburn Pathological Laboratory was created, named after the hospital’s longtime professor of morbid anatomy and special pathologist, Isaac Wright Blackburn, who specialized in gross pathology of the brain. While the laboratory had many directors over the years, none are more famous or notorious as Walter Jackson Freeman II, pioneer of the transorbital lobotomy.

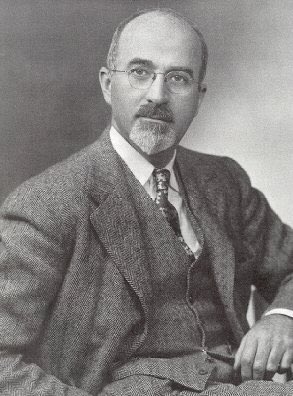

Walter Freeman was born on November 14, 1895, and raised in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, coming from a family of successful doctors. Freeman’s grandfather was William Williams Keen, the first brain surgeon in the United States and known in the medical field worldwide for inventing several new procedures in brain surgery including drainage of the cerebral ventricles and removals of large brain tumors. In 1887, Keen also performed the first successful removal of a brain tumor by drilling a hole into the patient’s skull and manually removing the tumor with his bare hands. He was in charge of a team of surgeons that performed a secret surgical operation to remove a cancerous jaw tumor on President Grover Cleveland in 1893. Keen was also part of the team that diagnosed President Franklin D. Roosevelt with polio.

Freeman studied attended Yale University beginning in 1912 and graduated in 1916. He then moved on to study neurology at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. While attending medical school, he studied the work of William Spiller who is credited worldwide as being the founder of neurology. Freeman applied to work alongside Spiller in his hometown of Philadelphia but was rejected. Instead, Freeman relocated in 1924 to Washington D.C. at the recommendation of his grandfather to take charge of Blackburn Pathological Laboratory at St. Elizabeths Hospital. After witnessing the pain and distress suffered by the patients at the hospital, and with the treatments of the time being electroshock therapy, hydrotherapy, and some limited psychotherapy offering little recourse, Freeman set out to find a physical cause for these illnesses. Although it should be noted that his feeling towards the patients was more out of disgust and shame, describing them in his own words, “[They inspire] a weird mixture of fear, disgust, and shame. The slouching figures, the vacant stare or averted eyes, the shabby clothing and footwear, the general untidiness—it all aroused rejection rather than sympathy or interest.”

Primarily working in the hospital’s morgue, Freeman had an endless stream of patients as mental hospitals at the time all suffered from overcrowding, described as large warehouses for the mentally ill. He performed thousands of autopsies at St. Elizabeths with one study claiming he examined nearly 1,500 cadavers of schizophrenics. He was known to hoist the bodies up by their ears and lay them against the morgue wall to measure them. Freeman was an entertainer and a showman, at times hosting an audience in the autopsy theater and “[holding organs] up—still dribbling blood—so that even his students in the back row could see, ” as Freeman wrote. Years earlier, he had removed a crude, primitive cock ring from a patient’s penis, had his family insignia carved onto it, and wore the ring around his neck as a badge of honor.

Freeman left St. Elizabeths in 1933 at the height of the Great Depression when most mental hospitals, including St. Elizabeths, were suffering financially while Freeman’s private practice was actually growing, ever worried how his colleagues outside the hospital would perceive him. Freeman wrote, “The attitude of the physicians in Washington towards St. Elizabeths was one of grudging admiration for their scientific achievements tempered by a feeling of strangeness to which the staff responded with feelings of isolation and lack of appreciation. I never regretted the decision to leave.” Decades later, he would donate copies of his works to the hospital, inscribing in them, “To St. Elizabeths Hospital, where I worked 1924-1933, to find some answers to the problem of mental disorder, and where more problems arose than were ever answered.”

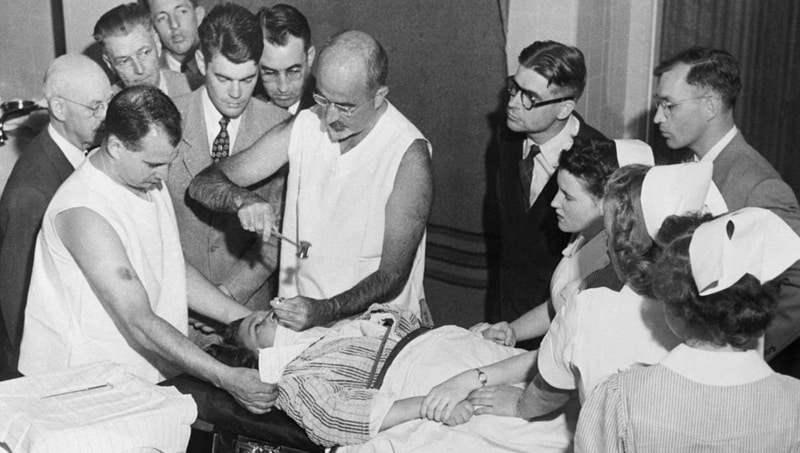

On November 12, 1935, a new psychosurgery procedure was performed in Portugal by neurologist and physician Egas Moniz. Intended to treat mental illness, the “leucotomy” involved removing small corings of the patient’s frontal lobes. Walter Freeman was the first to congratulate Moniz and the first doctor to recommend the procedure stateside. Freeman took Moniz’s work, modified the procedure, and renamed it the “lobotomy” which instead of taking corings from the frontal lobes, a lobotomy severed the connection between the frontal lobes and the thalamus. Freeman enlisted neurosurgeon Dr. James Watts not only shared Freeman’s beliefs but also because Freeman had lost his license to perform surgery himself after his last patient died on the operating table. On September 14, 1936, Freeman directed Watts through the very first prefrontal lobotomy in the United States on Alice Hood Hammatt. By November, only two months after performing their first lobotomy surgery, the duo had already performed 20 procedures. By 1942, they had performed over 200 lobotomies claiming 63% of patients had improved following the procedure, 24% were reportedly unchanged, and 14% were made worse or died. One of these patients was Rosemary Kennedy, sister of President of the United States John F. Kennedy and Senators Robert F. Kennedy and Ted Kennedy, who was ordered a lobotomy in 1941 by her father due to her violent mood swings and seizures. The procedure was a failure, leaving Rosemary with the mental capacity of a two-year-old and unable to walk or speak intelligibly. A short film featuring Walter Freeman and Dr. James Watts performing a prefrontal lobotomy can be viewed here.

Seeking to relieve himself of the complications associated with conventional brain surgery, Freeman heard of an Italian psychiatrist named Amarro Fiamberti who operated on the brain through his patients’ eye sockets, allowing him access to the brain without having to drill a hole into the skull. Inspired by Fiamberti’s work and without the knowledge of participation of Watts, Freeman developed the “transorbital lobotomy” which was performed by inserting an ice pick into the corner of each eye-socket, hammering it through the thin bone there with a mallet, and moving it back and forth, severing the connections to the prefrontal cortex in the frontal lobes of the brain. The new procedure was done in less than 7 minutes as opposed to a prefrontal lobotomy which took upwards to an hour, all while under a coma brought on by a machine that sent a jolt of electricity through the patient’s brain, inducing a seizure, and knocking them out. This method also did not require a neurosurgeon and could be performed outside of the operating room, allowing Freeman to broaden the use of the procedure which could be performed throughout the United States at mental hospitals which were overpopulated and understaffed. Watts opposed the cruelty and overuse of transorbital lobotomy, believing that lobotomies should always be the last case scenario and should only be performed by a trained surgeon. He soon left the practice that he and Freeman jointly established.

Following the development of the transorbital lobotomy, Walter Freeman took the procedure on the road, traveling the country in his camper-van visiting mental institutions, performing lobotomies, and preaching the positive claims which comes with a lobotomy. It should be noted that while many people claim he named his van the “lobotomobile”, there is no evidence to support the myth. Hospital administrators were swayed by Freeman’s claims of success and his showmanship as he was always a showman since his days at St. Elizabeths. In one instance in 1951, a patient died as Freeman stopped mid-procedure to pose for a photograph, leaving the pick in the patient’s brain which slowly slid further inward. Freeman also boasted having lobotomized 228 patients in 12 days while in West Virginia, charging just $20 a procedure. Not only did he visit hospitals, but Freeman also made house calls as well, performing lobotomies on housewives and drunkards. By his own count, Freeman performed over 3,500 lobotomies during this time. He had instructed psychiatrists how to perform a transorbital lobotomy and some 40,000 lobotomies were performed in the United States.

Lobotomy fell out of favor in the mid-1950s and early-1960s with the introduction of Thorazine, the first anti-psychotic medication pitched as a “chemical lobotomy” without causing any physical damage and with the benefit of stopping the medication if it did not help the patient. Freeman was unimpressed with the new medication, which spoke more about his ego and stubbornness. In 1967, he performed his last lobotomy on Helen Mortensen, a patient he had lobotomized two times already. Unfortunately, this time she died as her brain hemorrhaged and died three days later. Freeman himself died in 1972 of colon cancer, firmly believing he had done much good in his life.