Clayborn Temple is a historic church with national significance due to its role in the events of the Sanitation Workers’ Strike of 1968. The church started in 1888, the congregation of Second Presbyterian Church, decided to purchase a lot on the corner of Pontotoc and Hernando for the construction of their new building. Ground was broken for the construction on February 2, 1891, and the cornerstone of the church was laid on May 14. Sunday, January 1, 1893, the church held its dedication service. All the Presbyterian pastors of the city joined the congregation for the service.

This Romanesque Revival ecclesiastical architecture has cross-gabled roofs, constructed of limestone blocks, rusticated externally with heavy timber framing members forming the roof trusses, nave ceiling with wood beams that are suspended from the roof trusses by 2 x 4 studs. It has several unique features, for instance, the chancel is situated in the corner rather that the center of the sanctuary. When Second Presbyterian dedicated its new sanctuary on January 1, 1892, it was the largest church in America south of the Ohio River.

The congregation moved to East Memphis and sold the building to the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1949. It was renamed Clayborn Temple, named after AME region Bishop J.M. Clayborn.

Throughout the 1960s, Clayborn Temple served as the city’s staging ground for the civil rights movement, particularly the organizing headquarters of the Memphis Sanitation Strike. Memphis Labor Unions had tried for years to reform Memphis Public Works policies that included discrimination, unfair working conditions, and drastically insufficient wages.

On February 1, 1968, Echol Cole and Robert Walker were crushed to death while riding in the back of a garbage truck when the hydraulic ram was set off, thought to have been caused by a shovel that was jarred loose and crossed some electrical wires.

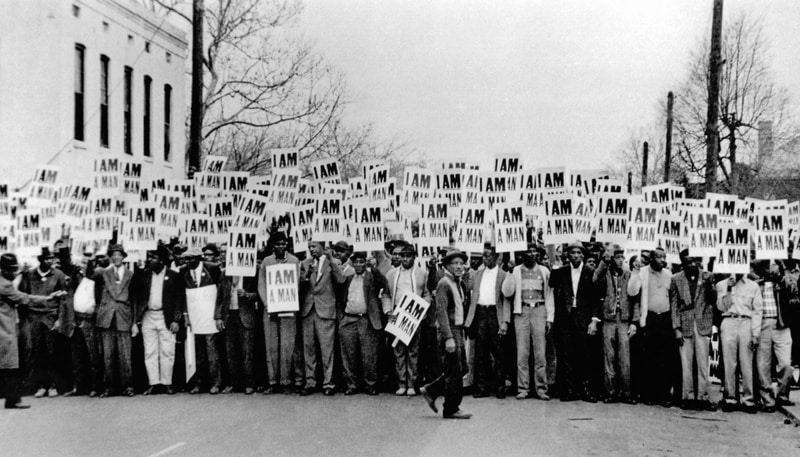

On February 12, 1968, 1,300 sanitation workers went on strike from the Memphis City Department of Public Works, citing the recent work-related deaths of Cole and Walker and years of poor treatment, discrimination, dangerous working conditions. Every day from then on, the strikers marched 1.3 miles from Clayborn Temple to City Hall, carrying signs which read “I AM A MAN”. The strikers received support from local organizations such as Mallory Knights, the Invaders, and Community On the Move for Equality (C.O.M.E.), which was a group of 150 local ministers led by Reverend James Lawson.

Clayborn Temple’s ministers gave support in however way they could. Reverend Ralph Jackson, the director of the AME Minimum Salary building next door to Clayborn, gave impassioned speeches to the supporters of the strike at Clayborn. Reverend Malcolm Blackburn was considered the movement’s most consistent white supporter and opened Clayborn’s offices, classrooms, and sanctuary to host the strategy meetings and community gatherings throughout the strike.

In March 1968, Reverend Lawson and C.O.M.E. invited Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to Memphis to shine a national spotlight on their efforts in the fight for economic justice. Dr. King arrived on March 18 and addressed a crowd of over 25,000 people, the largest indoor gathering of the civil rights movement. King pledged to return to Memphis on March 22 to lead a protest through the city. Unfortunately, a snowstorm prevented King from reaching Memphis and causing the march to be postponed until the following week.

King arrived late on March 28 to find a massive crowd of over 15,000 in chaos. Lawson and King led the march together, down Beale Street to City Hall. After marching only half a mile, the protest became violent when some of the youth began breaking windows. King called off the demonstration and was rushed back to his hotel. As looting and rioting quickly followed, Reverend Lawson urged the protesters to return to the church. Police reacted brutally to the riot, attacking both violent and peaceful marchers with tear gas and clubs. Police followed the crowd to the church, shooting tear gas canisters into the sanctuary and beating people as they lay on the floor gasping for air. Mayor Henry Loeb III declared martial law and brought in 4,000 heavily armed National Guard troops to quell any further unrest. At the end of the day, 280 people had been arrested during the riot, and 60 were reported injured. Stores in the black section of town were looted and burned. The only fatality of the day was 16-year-old Larry Payne, who was shot in the stomach with a shotgun by a police officer after being suspected of looting. Despite police pressure to have a private closed-casket funeral in their home, the family held the funeral at Clayborn Temple on April 2nd and had an open casket.

King considered not returning to Memphis, having been unaware of the division within the community, particularly of a black youth group known as the Invaders who were accused of starting the violence. He finally decided that if the nonviolent struggle for economic justice was going to succeed, it would be necessary to follow through with the movement there. King returned on April 3rd and spoke to a group of dedicated sanitation workers, delivering his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” address. The following evening on April 4, 1968, King was booked in Room 306 at the Lorraine Motel. As he stood on the balcony, he was fatally shot by James Earl Ray from a rooming house across the street using a Remington rifle. The assassination led to a nationwide wave of race riots, the greatest wave of social unrest the United States had experienced since the Civil War.

With riots raging across the country and the fear of rioting occurring in Memphis, Mayor Loeb still refused to concede to the union’s demands. On April 8, a completely silent march with Coretta Scott King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference attracted 42,000 participants. It wasn’t until President Lyndon B. Johnson send his James Reynolds, undersecretary of labor, to Memphis to help resolve the strike that negotiators finally reached a deal on April 16th, with a settlement that included union recognition and wage increases, bringing the strike to an end.

In 1979, Clayborn Temple was added to the National Register of Historic Places for its architectural significance and was upgraded to national significance for its role in the sanitation strike. The AME congregation continued to worship in Clayborn until its closure in 1999 due to its congregants moving away from downtown, similar to Second Presbyterian before it

The church sat abandoned for years until October 2015, when a group known as Nonprofit Neighborhood Preservation Inc. purchased the building to return the church to religious, educational and community uses. Services and events are currently held there, but the group plans to have restoration completed by April 2018, in time for the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. You can visit their website at www.claybornreborn.org.