In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many workers including those in the steel industry faced unsafe working conditions, long hours, and low wages. Unions were organized to address these issues but they were hardly successful in improving workers’ conditions. The situation improved briefly during World War I as companies were concerned with strikes breaking out at a time when wartime production was at its peak. In the wake of the war though, conditions regressed and even worsened as inflation made it difficult for workers for their families. Many workers went on strike during this period hoping to force their employers to improve working conditions and raise wages.

The largest strike occurred in September 1919 among steel mill workers in the Midwest, many of which worked for the largest employer in the area, U.S. Steel. Known as the Great Steel Strike of 1919, it eventually involved more than 350,000 workers who demanded higher wages, eight-hour workdays, and recognition of unions. The strike however proved to be a colossal failure as workers misjudged the lengths steel company executives and plant managers would go to break the strike. The post-war Red Scare allowed steel companies to sway public opinion. Pamphlets were published exposing one of the leaders of the strike, William Z. Foster, as a prominent advocate for socialism, claiming this was evidence that the steelworker strike was being led by communists and revolutionaries. They also played on nativist fears noting that many of the steel mill workers on strike were immigrants. At the same time, between 30,000 and 40,000 unskilled African-American and Mexican American workers were brought to work in the mills. Rumors were spread that the strike had collapsed pointing to operating steel mills as proof that the strike had ended.

As luck would have it, President Woodrow Wilson suffered a stroke on September 26, 1919, that prevented government intervention. The federal government’s inaction allowed state and local authorities and the steel companies to crush the strike by force. In Pennsylvania, police beat picketers and dragged strikers from their homes, throwing them in jail only to be promised release if they agreed to return to work. In Delaware, company guards were deputized who arrested strikers of fake weapons charges. Police and strikers clashed in Gary, Indiana, prompting the U.S. Army to intervene, taking over the city on October 6, 1919, and declaring martial law. Throughout the strike, telegrams and letters were sent to U.S. Steel chairman Elbert Gary in order to come to an agreement but he refused to settle. Steel mill workers in. By the end of November, workers were back at their jobs in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. The strike officially collapsed on January 8, 1920. Although the strike failed, Elbert Gary gave a small peace offering to U.S. Steel workers a welfare program that included pensions, and a profit-sharing plan. Under his direction though, the steel mills continued to run 12 hours a day, seven days a week.

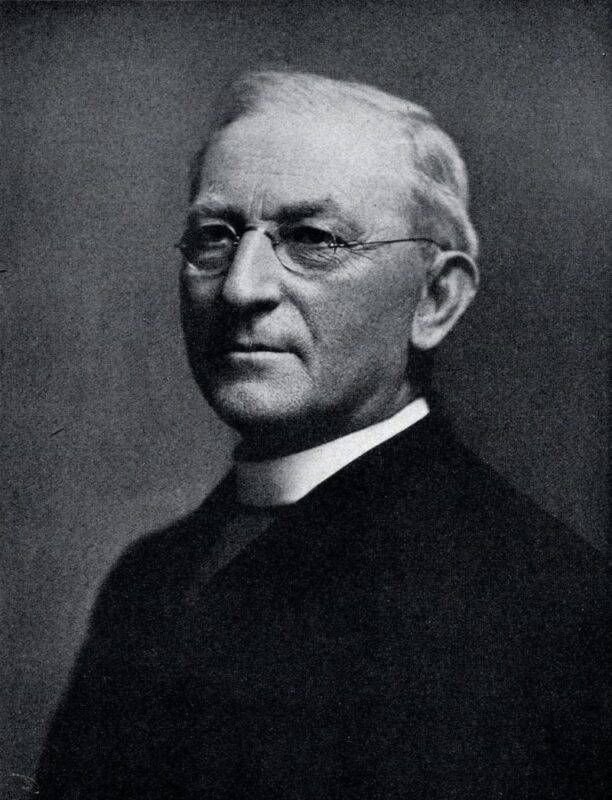

Mexicans first came to Gary during the Steel Strike of 1919 and continued to be hired in the years that followed. In the 1920s, Mexicans became the largest population of immigrant steelworkers in Gary. The bishop of nearby Ft. Wayne, Indiana, Herman J. Alerding announced the need for a facility “to care for the social needs of foreign-born Catholics” in Gary. In 1920, Alerding appealed to Elbery Gary to provide financial support for a Catholic settlement house claiming such a facility would result in better relations between employers and employees. He also added that the Americanization of immigrant workers was not only good to fight back against atheism, but against communism as well. In February 1921, U.S. Steel sent Aderling a contribution of $100,000. Alerding earmarked $30,000 of the donation for St. Anthony’s Chapel, the first church for the immigrant community. The rest of the donation would go towards the establishment of a settlement house to support the Irish, Italian, and Mexican immigrants of Gary.

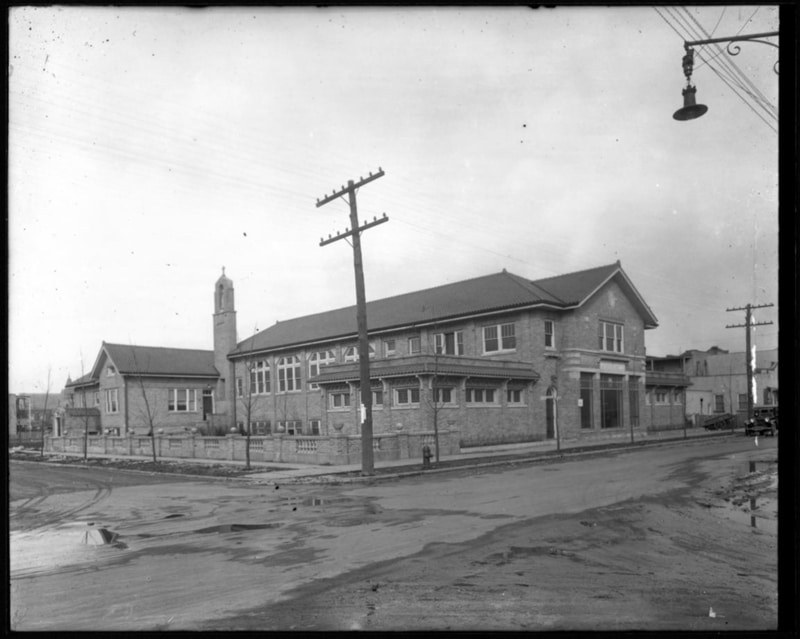

Construction of the Judge Gary-Bishop Alerding Settlement House began in March 1923 at the cost of $75,000. To commemorate the grand opening of the settlement house, a week-long celebration was held which included a circus and an opportunity for Gary residents to win daily prizes such as gold and even a Rickenbacker automobile with the official dedication occurring on May 18, 1924. The house was built next to Froebel School, one of the first schools in Gary to integrate whites, blacks, and immigrant students, in order to establish and foster a comfortable minority community. The building included forty boarding rooms, multiple classrooms, an ice cream parlor, a bowling alley, a pool with boys and girls showers, and a large auditorium that doubled as a gymnasium. The second floor had a clinic staffed by doctors and nurses from nearby Mercy Hospital.

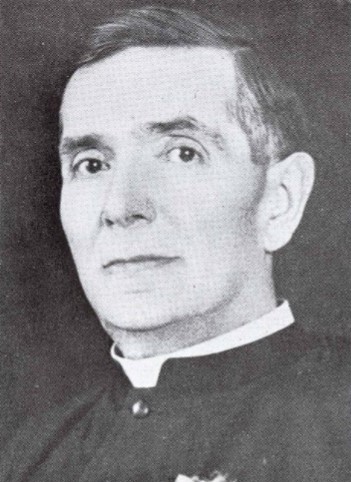

The director of the facility, Reverend John Baptiste DeVille emigrated from Italy to Pennsylvania and ran a successful parish before moving to the Holy Angel Catholic School in Gary in 1910. Bishop Alerding assigned DeVille to spearhead the Americanization efforts. He began by publishing the “Good Samaritan“, a monthly newsletter featuring positive religious messages with pro-steel and Americanization undertones. Despite the settlement house opening with much fanfare, it quickly lost community support. Bishop Alerding died on December 6, 1924, following a car accident, and his successor Bishop John Noll was unsupportive of the settlement house declaring it an “an immense burden on the diocese.” In 1925, DeVille requested another $30,000 from U.S. Steel for the completion of the chapel. The steel company reluctantly sent DeVille a check for $30,000 with a note attached stating it would be the last donation he would receive from them. Mexican immigrant steelworkers did not respond well to DeVille’s effort to enforce political and religious conformity and he eventually admitted defeat in his failure to Americanize the workers, although in a rather racist announcement. In 1927, De Ville gave a speech to the Rotary Club of Gary proclaiming, “We have shut out the European immigrants and have accepted the uncivilized Mexican immigrant in his place.” He also added, “You can Americanize a man from southeastern and southern Europe, but you can’t Americanize a Mexican.” Following the speech, attendance at the settlement house had fallen drastically and DeVille was forced to step down from his position of director in 1930. Having returned to Italy, he later died in 1932.

Reverend John Costello was assigned the director of the Gary-Alerding Settlement House on February 6, 1930. DeVille left Costello in a difficult position having done irreparable damage among Gary’s immigrant community and funding was scarce. The decision was made to transition the settlement house from a cultural center to a relief station for those suffering during the Great Depression. This decision allowed them to cut spending on programs and events while still providing for the community in some way. Hundred were fed daily from the house’s soup kitchen, clothes and shelter were provided for those in need, and job placement services were offered. Father Costello served as director until June 1935.

Bishop John Noll appointed Reverend Frederick J. Westendorf to succeed Father Costello as director of the settlement house. Westendorf briefly worked alongside Costello having been appointed his assistant a year prior in June 1934. Under his leadership, classes and recreational programs which had been cut during the Great Depression were restored. It was also through his efforts that the settlement house became a member of the Gary Community Chest which provided over half of the house’s operating and maintenance costs. In 1938, he joined the National Guard unit in Gary but continued acting as director of the settlement house having gained a reputation in the community for his work with Gary’s youth. In January 1941, he was sent to Camp Shelby in Mississippi where he was to stay for one year for active field training. After it was found that he would be leaving the settlement house, Westendorf received nearly 200 letters from city officials, businessmen, journalists, and priests, and others expressing their sincere regret at his departure. He would go on to achieve the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and served in World War II as Division Artillery Chaplain of the 38th Infantry Divison. After the war, he returned to Gary where he continued work with the Catholic church in Gary, Indiana until his death in 1963.

In 1943, Reverend James I. Cis was made director and brought back luxuries such as ice cream, bowling, and billiards. The settlement house became so popular within the community that some neighborhood kids began referring to themselves as the G.A.S. (Gary-Alerding Settlement) House Gang. By 1947, over 53,000 people were visiting the house annually and over 4,300 children enrolled in summer camps held by the church. After Father Cis left the house in 1953, its popularity and reputation would free fall.

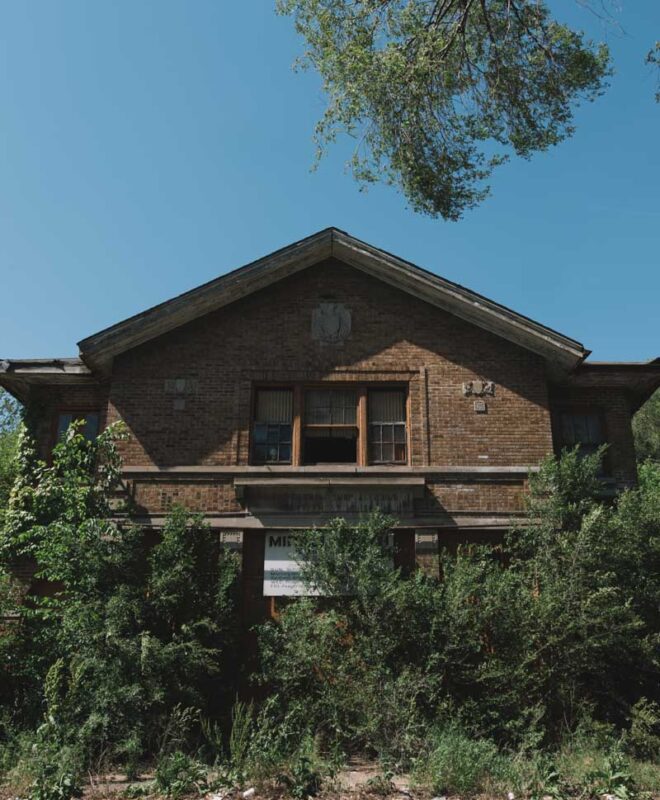

In the years that followed, the house’s budget was cut due to the hardships brought upon the diocese as the city as a whole declined. Donations to the house allowed its directors to focus on feeding programs having been recognized as having “the nation’s first non-school feeding program” in a 1968 article. It was also announced that 5,476 students were in one month. Despite the good press, it was overshadowed by its reputation as a safehouse for gang members and troubled youth who would take advantage of the religious protection offered there, usually after committing a crime. Reverend Francis M. Lazar served as director from 1967 to 1970 and would be the Gary-Alerding Settlement House’s last. The house remained open for a year without a director in charge and by that point, the building has fallen into disrepair and gang activity had only worsened. Looking to cut costs, the diocese closed it down in 1971. For a while, it functioned as a church, the Miracle Faith Word Center, which thrived under the leadership of Dr. Hortense Trotter. Like all things in Gary though, that too closed down and the Gary-Alerding Settlement House has remained vacant ever since.

Sources:

The History of St. Mark’s Parish, Gary, Indiana. Indiana State Library. Retrieved December 8, 2021

The Gary-Alerding Settlement House. Sometimes Interesting. June 6, 2013