James Ward Packard and his brother William Doud Packard founded the Packard Electric Company in 1890 where they manufactured incandescent carbon arc lamps. James Packard was disappointed with a Winton Car Company automobile he purchased and being a mechanical engineer, believed he could build a better automobile than the Winton cars. After his suggestions for improvements were ignored by Alexander Winton, founder of the Winton Motor Carriage Company, he formed a partnership with his brother and Winton investor George Lewis Weiss called Packard & Weiss in 1893. From their factory in Warren, Ohio, the first Packard automobiles were built in 1899. An original Packard, reputedly the first manufactured, was donated by a grateful James Packard to his alma mater, Lehigh University, and is preserved there in the Packard Laboratory. Another is on display at the Packard Museum in Warren, Ohio. In 1900, the company incorporated as the Ohio Automobile Company.

In 1902, Henry Bourne Joy, a member of one of Detroit’s oldest and wealthiest families, was on a trip to New York when he happened to see two Packards chase down a horse-drawn fire wagon. Fascinated by what he witnessed, he purchased the only Packard in the city. Impressed by its reliability, he visited the Packards at their headquarters in Warren, Ohio, and soon enlisted a group of investors that included his brother-in-law, Truman Handy Newberry, and Russell A. Alger Jr. On October 2, 1902, the group refinanced and renamed the Ohio Automobile Company to the Packard Motor Car Company, with James Packard as president and Alger later serving as vice president.

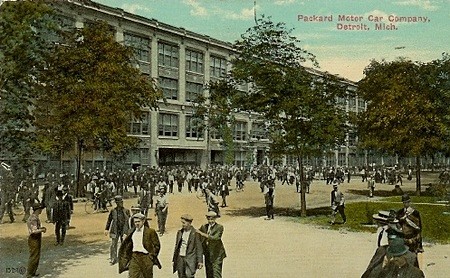

The company moved to Detroit where Joy approached Albert Kahn, a young architect at the time who, along with his brother Julius Kahn, developed a new style of construction whereby reinforced concrete replaced wood in factory walls, roofs, and supports. Kahn was tasked with designing and building the world’s first reinforced concrete factory. The Packard plant opened in 1903 and contained 10,000 square feet of floor space and at the time was considered the most modern automobile manufacturing facility in the world. Considered massive in scale when it first opened, the plant continued expanding until construction was completed in 1911. By 1908, when an enlargement for the construction of trucks was announced, the factory was already six times larger than when it first opened and occupied over fourteen acres of space. By its completion, the plant was the largest auto plant in the United States boasting over 3,500,000 sq ft and occupying 40 acres of land.

Following the company relocation to Detroit, the Packard brothers focused on making automotive electrical systems via the Packard Electric Company. Henry Joy served as general manager of the Packard Motor Car Company from 1903 to 1909, president from 1909 to 1916, and chairman of the board from 1916 to 1926. Under Joy’s leadership, Packard gained a reputation for technology and high-luxury. Packard automobiles featured innovations such as the modern steering wheel and air conditioning in a passenger car. Packard also featured the first production 12-cylinder engine adapted from the development of the renowned Liberty L-12 aircraft engine. During the 1920s, Packard solidified its reputation for exceptional engineering and became known as one of the highest quality luxury vehicles produced in the United States. The company also began the transition from hand assembly to an assembly line and installed a multistory automated assembly line in the 1930s to accommodate the plant’s current structures which had become outdated in the face of new technology.

In 1942, Packard joined other automotive factories in halting all car production and focusing on manufacturing for the WWII effort. The plant churned out Packard V-1650 Merlin engines which powered the North American P-51 Mustang fighter plane, as well as V-12 marine engines for American PT boats and some of Britain’s patrol boats. To keep up with demand, the plant was further expanded and upgraded.

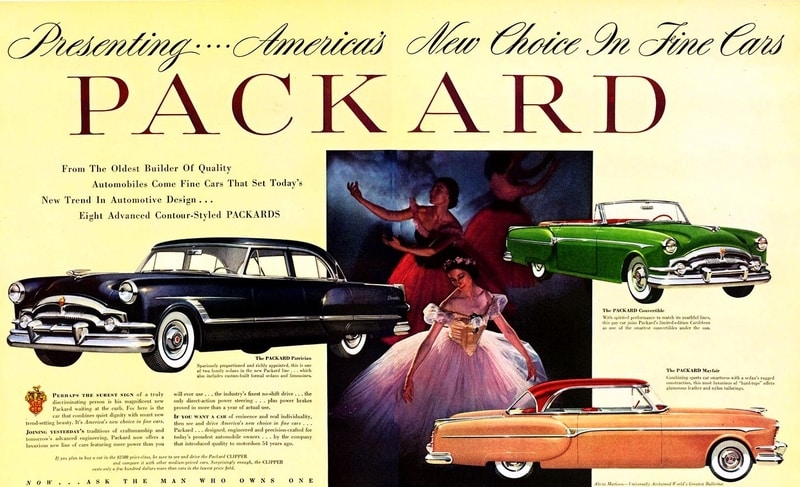

In late-1945, the plant resumed production of civilian automobiles and even though Packard was in excellent financial condition following the war, several managerial decisions and Packard’s inability to compete with other auto manufacturers led to its demise. In order to compete with new car designs being released by Packard’s rivals such as GM and Lincoln, Packard introduced the Clipper just eight months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Packard was one of only three automakers that had introduced all-new designs in 1941, the other two being Ford and GM, although GM made such few of their 1941 models that were looked relatively new when production resumed in 1946. Packard resumed production of the Clipper after the war but by then, it was considered outdated as the new envelope bodies started appearing, led by Studebaker and Kaiser-Frazer. While Ford went on to totally redesign the Ford and Mercury in 1949, Packard went with a “bathtub” design for their 1948-1950 Clippers which was welcomed with mixed reviews being described as a “pregnant elephant” by many. GM Cadillac’s new 1948 models had sleek, aircraft-inspired styling which made Packard’s design look old-fashioned.

Moreover, Cadillac had also introduced a brand-new OHV V8 engine in 1949 which gave their cars a reputation for performance that Packard’s dependable, but aging inline eight engines couldn’t match. During this time, Cadillac was among the earliest U.S. automakers to offer an automatic transmission, the Hydramatic in 1941. Packard caught up by developing the Ultramatic in 1949 but could not compare to GM’s Hydramatic for smoothness of shifting, acceleration, or reliability. The resources spent on Ultramatic deprived Packard of the chance to develop a badly needed modern V8 engine. With the combination of the lower-priced Packards leading sales and impacting the prestige of their higher-end brethren and some questionable marketing decisions, Packard was no longer considered the “king” of luxury vehicles and that title would be stolen by the rising Cadillac. Packard’s image was increasingly seen as old-fashioned and unappealing to younger customers and struggled to attract new buyers. Much of these decisions could be seen as the fault of Packard’s aged leadership who were reluctant to retire due to Packard’s lack of a pension plan for executives, thus blocking younger men from coming into power of the company.

On top of all this, independent automakers were caught up in the middle of a brutal sales war between the “Big Three”—General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler. Many of these manufacturers merged in order to stay alive such as the American Motors Corporation (AMC) which consisted of Nash-Kelvinator Corporation and Hudson Motor Car Company. In 1954, the Packard Motor Car Company merged with the failing Studebaker Corporation of South Bend, Indiana, to form the Studebaker-Packard Corporation and America’s fourth-largest automobile company. Using Studebaker’s larger dealer network and Packard’s cash position, the two companies hoped to stabilize and strengthen their product lines. As devised by Packard president James J. Nance and AMC CEO George W. Mason, the original plan was AMC would bring Studebaker-Packard into the fold to form America’s third-largest auto manufacturer, surpassing Chrysler. George Mason died before the proposed merger could be realized.

Packard attempted to salvage what it could and introduced a revolutionary new model in 1955 which, by their credit, was nearly universally praised. As the new models were ready to be produced, an old problem flared up. Due to Packard’s outdated Detroit plant, the company outsourced its body production to Briggs Manufacturing Company in 1941. After Briggs’ founded Walter Briggs had died in early-1952, his company was put up for sale by his family. Chrysler promptly purchased Briggs and notified Packard they would cease production of bodies for them in 1953 when their contract with Briggs expired. Packard was forced to move body production to a smaller plant in Detroit which proved too small and caused countless quality problems. Bad quality control hurt the company’s image and sales plummeted in 1956. Following a disastrous sales year, Studebaker-Packard entered a management agreement with the Curtiss-Wright Corporation. Curtiss insisted on making major changes. All of Studebaker-Packard’s defense contracts and plants where defense work was carried out were picked up by Curtiss, Packard production in Detroit was stopped and all remaining automotive efforts were shifted to South Bend. Packards continued being produced at Studebaker’s South Bend plant until 1958 and in 1962, Studebaker dropped the Packard name entirely.

Since 1958, multiple businesses have occupied portions of the Detroit plant. When the city of Detroit took possession of the property with the intent of demolishing it. By 2006, most tenants had vacated and it was 2010 that the final tenant of the Packard Plant, Chemical processing, left the site, leaving the structures completely abandoned. In 2013 investor Fernando Palazuelo purchased the plant for $405,000 with plans of rehabilitating the structures into a multi-purpose campus. In May 2017, Arte Express, the holding company for Palazuelo, held a groundbreaking ceremony for phase I of the project which will include the former 121,000-square-foot administrative building on the site. A portion of the plant owned by the city on the south side of the property was demolished in 2019. In October 2020, it was announced that the original redevelopment vision for the site had been abandoned, and Mr. Palazuelo would be placing the property up for sale, with an eye towards large-scale demolition to repurpose the site for industrial use.